Is College Board allowing third party advertisers, keystroke loggers, and behavioral analytics to track students? “Recording everything they do?”

With the move to online learning, many parents are asking edtech companies, “What are you doing with my child’s data?” That seems a reasonable question. As a parent myself, I have wondered how the College Board uses and monetizes students’ data. Similar to a recent investigation by Consumer Reports, I recently discovered that College Board allows third parties such as Facebook and advertisers such as Adobe Marketing, Google Ads, Bing Ads, Yahoo and more to track users on multiple College Board websites. However, in addition to these ad trackers, I documented where the College Board apparently utilized hidden analytics tools, including one that records everything a user does on a website and offers keystroke logging and “behavior tag” analysis of users. I also discovered that College Board apparently required typing samples from students, asked students to give College Board an unlimited right to use their AP written and oral responses, and College Board changed their AP Terms of Service after students agreed to them in Fall of 2019. I wonder how many parents or students know this about College Board.

The College Board, a signatory to the Student Privacy Pledge which promises not to sell students’ personal data for behavioral advertising and promises to only disclose data for educational purposes, is also the owner of the PSAT, SAT, and Advanced Placement (AP) exams. The College Board appears to be a very profitable “non-profit” that also receives considerable public subsidies. This report suggests the College Board is a hedge fund which has money in multiple offshore accounts, and has assets in excess of $1.1 Billion. According to 2018 tax records, College Board paid David Coleman, their CEO, an annual salary of over $1.5 Million, and paid multiple staff salaries in the $300-500,000 range, including Trevor Packer the VP of AP programs, whose annual salary in 2018 was $526,359. As seen in this letter to a parent, the College Board uses its non-profit status to claim exemption from California’s Consumer Privacy Act.

College Board sells licenses to access student data. Do they also sell student data for advertising purposes?

The College Board profits from selling exams but also profits from licensing students’ data. As we wrote in this 2017 Washington Post piece, the College Board profiles students’ geographic, attitudinal and behavioral information and sells licenses to institutions and researchers, allowing access to student data.

“The College Board sells licenses to access the data through a tagging service called College Board Search. The Segment Analysis Service™ is one of three featured tools of the Search, along with the Enrollment Planning Service™, and the Student Search Service®. These are “enhanced tools for smart recruitment.” The College Board’s Authorized Usage Policies states, “Student Search Service in connection with a legally valid program that takes such characteristics into account in furtherance of attaining a diverse student body.”…and allows college admission professionals to identify prospective students based on factors such as zip code and race and to “Leverage profiles of College Board test-takers for all states, geomarkets, and high schools.”

In December 2019, the College Board was named in a class action lawsuit for improperly obtaining and selling student data. The lawsuit, which was recently amended, mentions selling student data to targeted advertisers such as Facebook,

“While students were made to believe the results of these tests would significantly impact their futures, to College Board the tests served a wholly different purpose – i.e., to obtain highly valuable personal student information to benefit its own business interests and increase its revenues, which exceeded $1 billion in 2018. College Board obtained the students’ personal information using unfair and deceptive practices and then unlawfully released, transferred, disclosed, disseminated and sold the information. The deceptive practices used by College Board to obtain the personal information included: (a) misrepresenting that it did not sell the information; (b) misrepresenting that it only disclosed nonidentifiable information to third-party targeted advertisers such as Facebook; (c) requiring students to create online accounts for the purported purpose of registering for exams when, in fact, the online accounts provided College Board with a mechanism to obtain massive amounts of personal information that it then unlawfully disclosed and disseminated to third parties…If only one third party were to purchase the personal information of the 2.5 million children who take the AP Exams the total price would be $1,175,000. Obviously, College Board sells data to as many customers as possible.” [Emphasis added]

Recent changes to College Board’s AP platform: everyone must join online.

In August of 2019 the College Board changed how students and teachers use Advanced Placement (AP) curriculum and assessments by creating new online tools, the online AP Classroom / MY AP account. According to the College Board,

“It all starts with joining the online system. This step unlocks new digital tools and resources that students, teachers, and coordinators can use throughout the year, including an AP question bank and Personal Progress Checks. … Students who don’t already have a College Board account must create one.” [Emphasis added]

The College Board AP Central website boasts “Everything streamlined. Everything online.” In creating the required online College Board account, AP students are asked to provide substantial personal information. Here is a non-exhaustive list: Student email address*, Student home address*, Student Date of Birth*, Student cell phone number, race, parent education level, parent name, parent email address, classes the student has taken or intends to take. (*=required) Note: the student MUST also agree to the privacy policy and Terms and Conditions* when creating this required account: “By submitting this information, you are accepting the Site Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy governing the College Board’s website.” Take it or leave it. College Board is the only company offering high school students an exam to earn college credit.

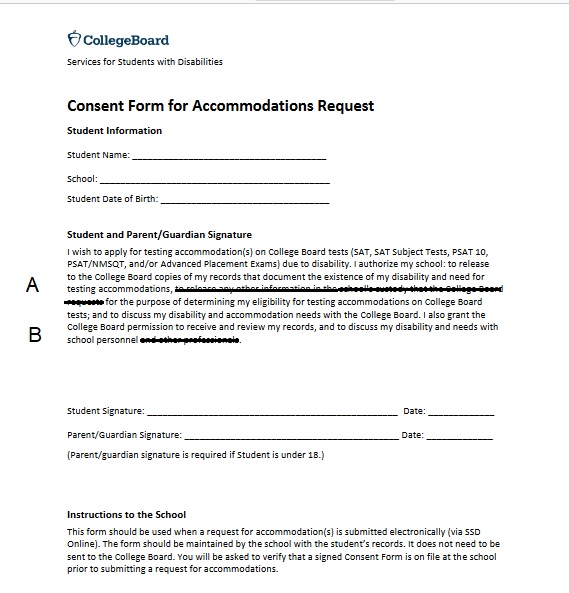

In the fall of 2019, College Board also began requiring school AP Coordinators to register students for the AP exams and electronically submit an AP Participation Form, with “a few final questions” and an AP Survey. As of this writing, I was unable to find the 2019-2020 AP Participation Form, final questions, or the AP Survey mentioned in the AP Coordinator’s Manual Part 1 and Part 2. What are schools agreeing to when they register students for AP exams? What are students agreeing to when they create an AP account, use AP Classroom, or take AP exams?

College Board has changed the AP Terms of Service/ Terms and Conditions since Fall 2019.

Since Fall of 2019, we have found at least 4 different versions of AP Terms for students. Which set of AP terms are students beholden to? Here is a capture of the October 2019 MyAP terms thatstudents could see and were required to agree to, when they created their online AP account; here is slightly different public version of MyAP terms. Here are the APCoronavirus terms, and here is a capture of the MyAP terms as of July 2020, that students see if they log into their MyAP account. Which set of AP terms are students agreeing to? Excerpts from this Fall 2019 version of MyAP Terms and Conditions state,

- “You acknowledge that it is not the responsibility of College Board to determine whether your school is required to obtain parental consent”

- “AP Student End Users. Any data provided about you may be used (in the aggregate and/or anonymously) for research purposes, to prepare research reports, and/or in AP Exam ordering and registration processes. Occasionally, College Board researchers and their subcontractors may contact students to invite their participation in surveys or other research. Data collected from the AP Classroom system could also be shared with researchers and partners.”

- “College Board does not serve Ads in the Services or use Customer Data for Advertising purposes.” See full version of these terms archived here.

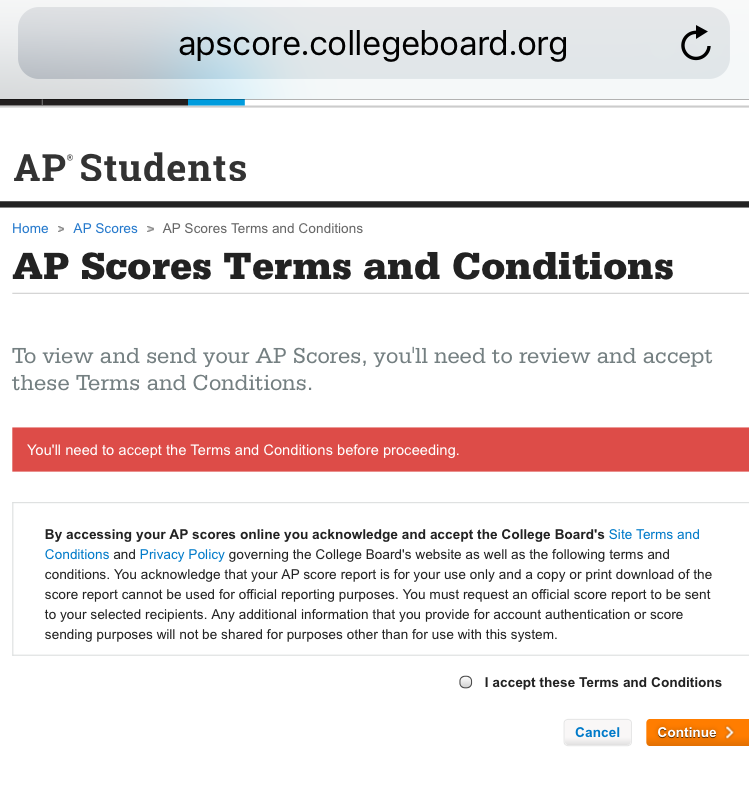

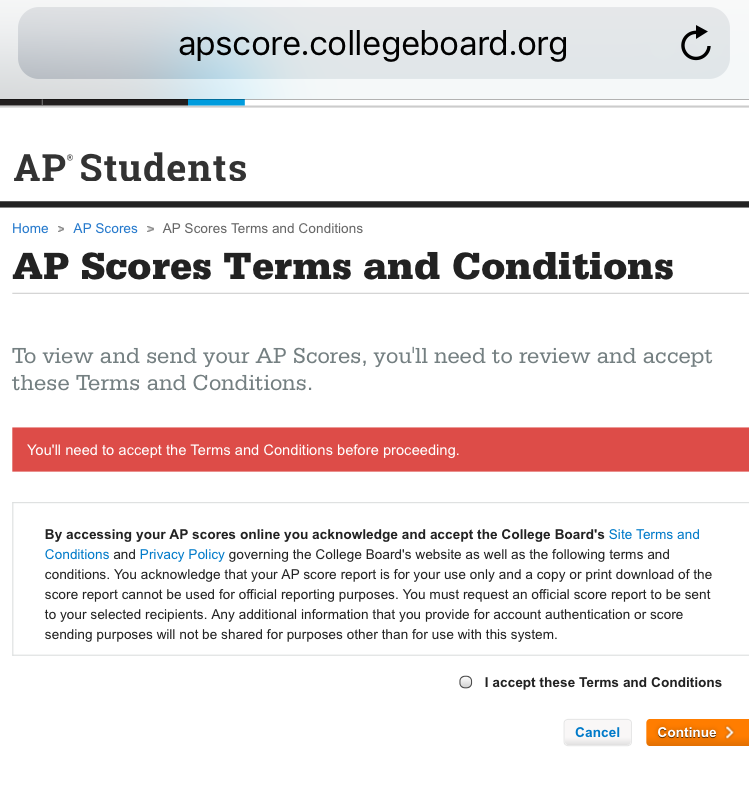

To view and send their AP scores, per screen capture above, students were required to agree to these new (July 2020) Terms and Conditions which added new language, including the following:

- “Students access AP Services as authorized users of their respective Schools. However, when Students take AP Exams, they do so in their personal capacities, and the scores they earn are their own. Accordingly, in order to take AP Exams, Students are required to enter into a separate agreement by accepting the AP Terms & Conditions prior to taking their first AP Exam.

- Similarly, when Students access College Board services that are not AP Services, Students again do so in their personal capacities, not as Students of School. Non-AP Services may include, but are not limited to, SAT® registration, college score sends, linking a College Board account to Khan Academy®, creating a college list on BigFuture™, or applying for a scholarship.

- AP Classroom and Pre-AP Classroom are hosted by Academic Merit, LLC, a third-party platform that is prohibited from using data collected on AP Classroom and Pre-AP Classroom for any purpose other than delivering services to College Board.

- College Board may use Data for its internal research purposes. College Board may also disclose aggregated and/or de-identified Data with trusted third parties.” [Emphasis added]

The new language in the July Terms says students who took the AP exam do so in their personal capacity–-this is concerning. The school had to register the students for the AP exams and the school had to agree to the Terms in the elusive Participation Form– so why do students suddenly have to agree to new Terms saying they took the exam at their personal capacity – AFTER the fact ? What is College Board trying to avoid?

Further, I find it problematic that students had to go onto the College Board website (apparently with ad trackers and analytics trackers) to even READ the AP Terms and Conditions. And in at least two cases, (October and July MyAP Terms), students actually had to submit personal information: create an account and log-in to see the MyAP Terms which they were required to agree to.

It makes my head spin trying to keep all these AP Terms and Privacy Policies straight. But imagine being a 16 or 17 year old, trying to navigate this. Should students be agreeing to all of these Terms and Conditions just to take an exam and see their scores?

Can students opt out of sharing their personal data with subcontractors and researchers? If College Board does not use customer data for advertising purposes, why are there several advertising companies tracking users on College Board websites? If the data are anonymous, why are researchers and subcontractors contacting students? Selling student data and targeted advertising are prohibited by the Student Privacy Pledge and by many state laws. Interestingly, this Bulletin for AP Students and Parents states College Board will not sell or share or rent student data; however, pay attention to the exceptions.

“Except as described in this publication, or to share with our operational partners for the purpose of administering testing services and generating score reports, the personal information you provide to College Board will not be sold, rented, loaned, or otherwise shared.” [Emphasis added]

Selling student data

This November 2019 Wall Street Journal piece, For Sale: SAT-Takers’ Names. Colleges Buy Student Data and Boost Exclusivity, reports that College Board sells student test score ranges, names, and demographic information,

“College Board sells lists of high-school students’ names, ethnicities, parents’ education and approximate PSAT or SAT scores, at 47 cents a name. Each year, 1,900 schools and scholarship programs buy combinations from among 2 million to 2.5 million names, College Board said, declining to say how many names in total it sells. Schools target combinations of geography, socio-economic class and academic interests. A college could buy a list of, say, soccer-playing Caucasian girls from Colorado, Wyoming and Montana who scored 1,200 to 1,300 on the PSAT, are interested in engineering and whose parents didn’t attend college.”

This case study from a College Board stakeholders’ workshop clearly lists “Buy Names –> Analyze” and “Purchase Flow”; other pages of the case study list tagging and analysis of student data by ethnicity, family income-band, socioeconomic communities, marketing zones and listing student names that have not been sold on any order.

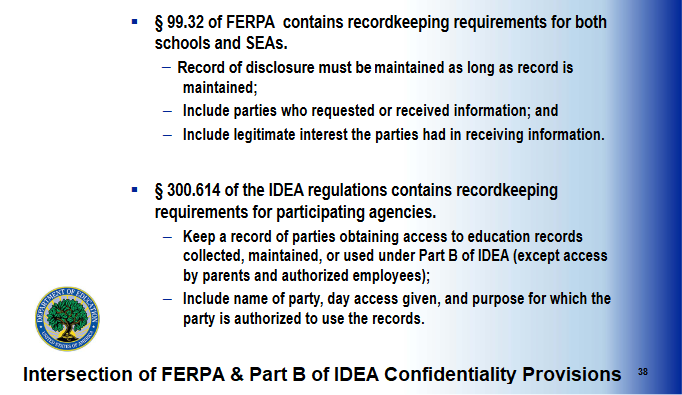

In May 2018, the U.S. Department of Education issued significant guidance that prohibits states or districts to allow testing companies like College Board to sell or re-disclose student assessment data, including test score ranges, without parent consent.

Regarding testing companies, their pre-test surveys, and student privacy, the U.S. DoE guidance states,

“In connection with these college admissions examinations, testing companies administer voluntary pre-test surveys asking questions about a variety of topics ranging from academic interests, to participation in extra-curricular activities, to religious affiliation. …the testing companies then sell this information to colleges, universities, scholarship services, and other organizations for college recruitment and scholarship solicitation.

…The administration of these tests and the associated pre-test surveys by SEAs and LEAs to students raises potential issues under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), the confidentiality of nformation provisions in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), the Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment (PPRA), and several recently enacted State privacy laws, and generally raises concerns about privacy best practices.”

“contracts between testing companies and SEA, LEAs, should include provisions assuring that before PII is disclosed nonconsensually, the testing companies (when acting on behalf of the SEA, LEA, or school) will comply with the privacy protections required by Federal law, specifically FERPA and IDEA. When contracting with the testing companies, SEAs, LEAs, and schools should also specify in their contracts that there is a general prohibition under both FERPA and IDEA regarding the unauthorized use and re-disclosure of PII from students’ education records (including any biographical or demographic information about the students provided by the SEA, LEA, or school to the testing companies, and the students’ test scores or test score ranges)”. [Emphasis added]

No Contract for AP?

In this October 2019 letter, I asked the Colorado Board of Education for help with transparency about the data collected and shared via the new online 2019-20 AP format. Colorado’s Student Data Collection Use and Security law requires contracted education providers and their subcontractors to be transparent about data elements collected, their purpose, how used and shared. However, as mentioned in the letter above, I could not find a single school or district in Colorado who had posted a signed AP contract with College Board. School administrators that I spoke to alleged their AP contract negotiations with College Board had stalled for over two years, and they were unable to get College Board to sign an AP contract.

Is College Board refusing to sign AP contracts because they don’t want to be transparent about their use of student data?

AP Exams Moved Online, at Home. College Board President said students’ cameras and microphone would be turned on.

For the first time ever, College Board announced that the 2020 AP exams would be administered online and students would take the AP exams at home. When explaining what this online, at-home exam would look like for students, on April 15, 2020 EdSurge quotes the College Board president, Jeremy Singer, as saying the camera and microphone will be turned on and the exam will use the same software as the pre-test Demo.

AP testing was chaotic and fraught with technical glitches

During the first week of the online AP exams, College Board frequently posted updates on Twitter. Students responded with frantic questions including asking why the College Board required a typing sample on the test, when they did not ask for a typing sample on the Demo. Thousands of stressed-out students reported that they were unable to submit their completed AP test because of technical glitches and problems with the online submission process. This May 20, 2020 Verge article entitled, “Students are failing AP tests because the College Board can’t handle iPhone photos” quotes a student commenting on the College Board’s tweet tips being too late to help. OneZero writes about Fake Tweets, Broken Tests, and a Misinformation Campaign: How The College Board Botched Spring Semester. The Washington Post Answer Sheet also wrote about the botched online AP tests; author Valerie Straus questions the actual number of students unable to submit their test responses.

The botched online AP tests resulted in another lawsuit against College Board.

The Washington Post Answer Sheet and Valerie Straus followed up on the subsequent class action lawsuit. The lawsuit on behalf of students who encountered problems taking the online AP exam, claims breach of contract and discrimination against students with disabilities. (The College Board added a new submission procedure during the second week of testing; this new procedure came too late for the many students who were unable to submit their exams the first week.) The amended complaint also alleges that College Board required students with disabilities to log into the College Board’s BigFuture website to check the status of their disability accommodations and also claims that College Board did not honor student accommodations for breaks,

“The lawsuit asks that the College Board accept any test answers from last week’s AP tests that can be shown to have been completed in time by time stamp, photo and email. It charges that the College Board ignored warnings that giving AP tests online would discriminate against students with disabilities and those who did not have access to technology or the Internet at home to take the exams. [College Board] instructed all students with disabilities who had applied for accommodations to log in to Defendants’ “Big Future” platform to find their accommodation decisions. Had M.W. not been disabled and searching for her accommodations, she would not otherwise have been required to log into Big Future. M.W.’s Defendants accommodations letter states that she is entitled to “extra breaks.” However, when changes to the AP Exam format were announced, M.W. learned that the at-home AP Exam format did not allow for any breaks whatsoever.”

It’s important to note that College Board’s BigFuture Scholarship Search collects students’ disability type, religious affiliation, citizenship status, ethnic and minority background and special conditions such as cancer or hemophilia. At the time of this writing, I could not find a specific privacy policy or terms of service for how BigFuture uses or shares this personal and sensitive information. However, this archived College Board website states that while College Board never shares disability status or test scores, they do share (sell licenses to?) test score ranges, including AP score range, if students opt-in to Student Search Services.

Practice, Practice, Practice: College Board tells students to take the online pre-test AP Demo.

To avoid testing glitches, students were instructed multiple times to go to the College Board website and practice with the exam Demo before their actual exam, to make sure they were familiar with the online format and to confirm their device and browser were compatible.

I took the online AP Exam Demo. I was shocked at what I saw.

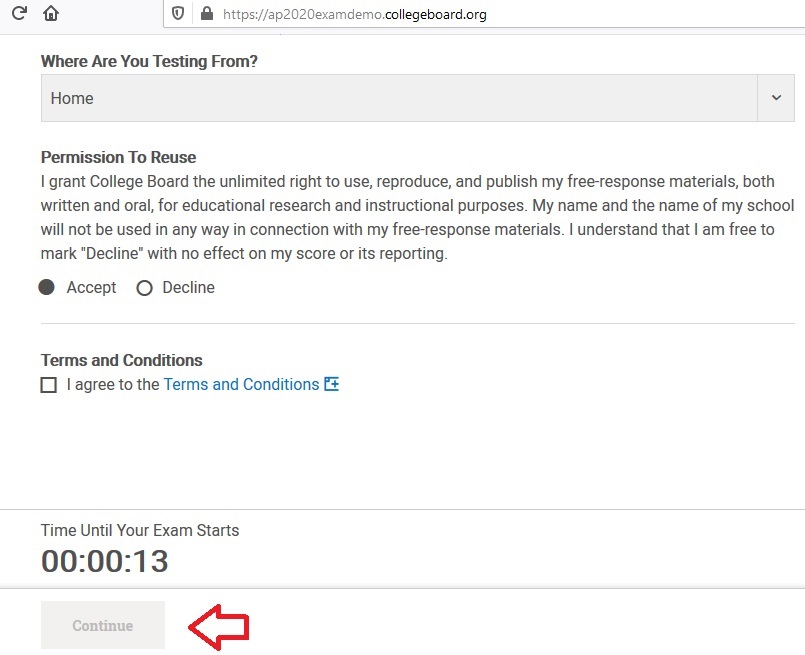

Granting College Board Unlimited Right to Use Student Data?

This permission to allow College Board unlimited right to use student data for educational research and instructional purposes was AUTO FILLED to “Accept”. I am told this same question, auto filled to “Accept”, also appeared on the actual AP exams. How many students declined this permission?

We know data can be re-identified or machine matched. (See here, here, here.) This permission notice only states that student name and school will not be used, but College Board collects a student’s date of birth, student ID, parent and student address, email address, cell phone, location, device information, etc. This permission for data use apparently includes oral responses; a person’s voice is personally identifiable (more on biometric data below). Will the College Board tell us how many students actually agreed to grant the College Board the unlimited right to use, reproduce, and publish their free response data? “Educational research” is very broad; can students ask to see how their data are used, shared, or profiled? Can a student change their mind, retract their consent and ask to have any shared data deleted?

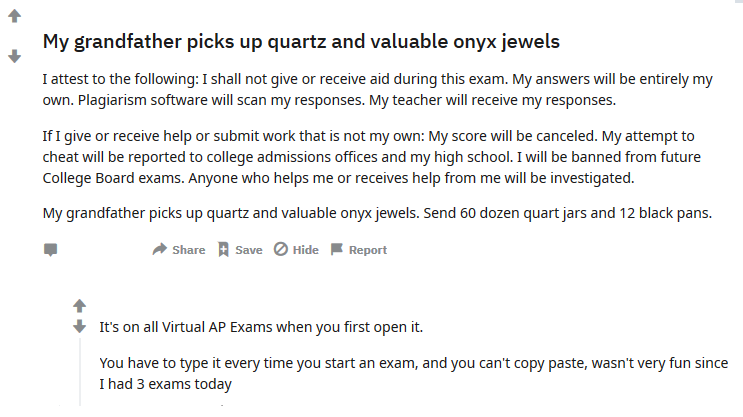

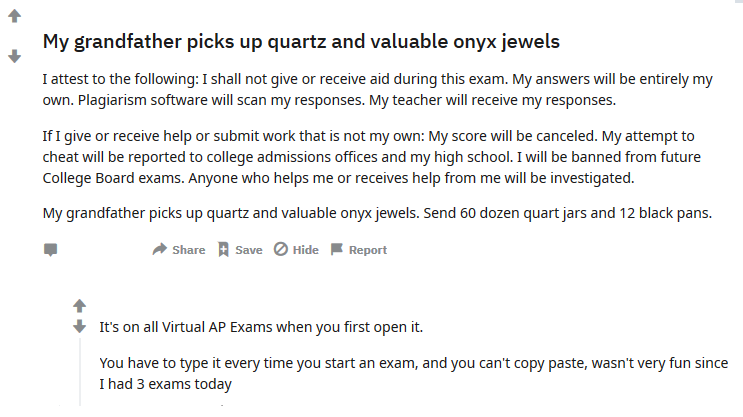

Required Typing Sample Before Every Online AP Exam?

Many students on Twitter and Reddit said they had to submit the same online typing sample for every AP exam. Students were apparently instructed to type the same short sentences about plagiarism, cheating, and how their grandfather picks up quartz and valuable jewels. These sentences used every letter of the alphabet, and students were told to copy them word for word, typing in their typical typing style during the 30 minute pre-test session. There was no typing sample on the AP Demo exam.

Your typing pattern is a biometric identifier, unique to you, like a fingerprint or DNA.

Many states have biometric privacy laws protecting voice and unique characteristics of an individual that can be used to authenticate a person’s identity (oral response data is mentioned in the consent for unlimited right to use data, above). Keystroke data are specifically protected under California Consumer Privacy Act. If students were asked to submit typing samples, did College Board obtain informed user consent where necessary and how are College Board or third parties using this biometric data? As this PC World article states, “AI-based typing biometrics might be authentication’s next big thing”,

“Identifying or authenticating people based on how they type is not a new idea, but thanks to advances in artificial intelligence it can now be done with a very high level of accuracy, making it a viable replacement for other forms of biometrics.”

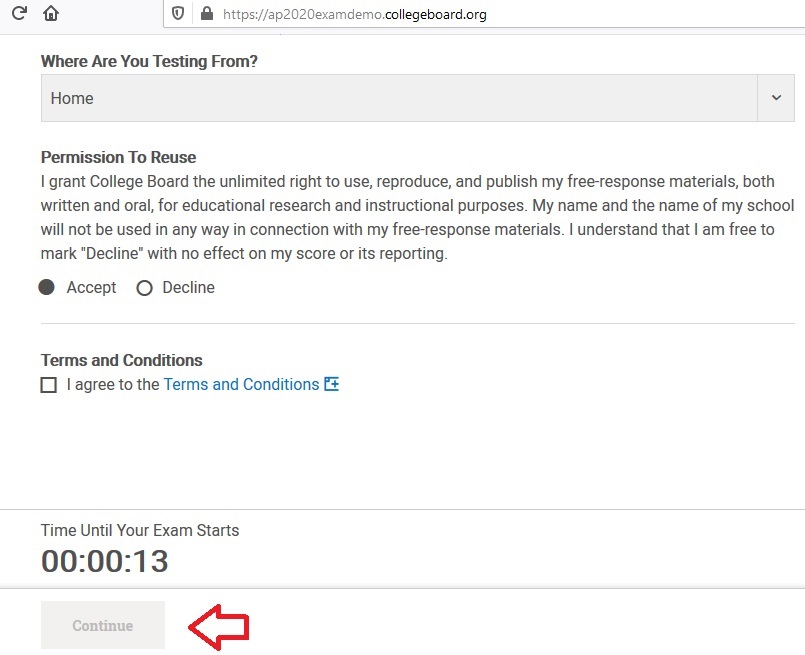

Finally, when taking the AP Demo, I had no choice but to accept the Terms and Conditions.

I couldn’t go on to complete the first question of the Demo exam, unless I checked yes. I had 3 minutes and 30 seconds to read and understand these long legal Terms and Conditions. I ran out of time; the clock expired, but the “Continue” box remained greyed-out until I clicked “I agree to the Terms and Conditions”. I am also told that students had to click “I agree” to the Terms and Conditions in order to complete the online AP exam. This type of “forced consent” feels more like entrapment. Will the College Board report the statistics on how many students even opened these Terms and Conditions, and how many students just clicked agree without opening the Terms? This Deloitte study found that in general, 97% of young people agree to conditions without ever reading them.

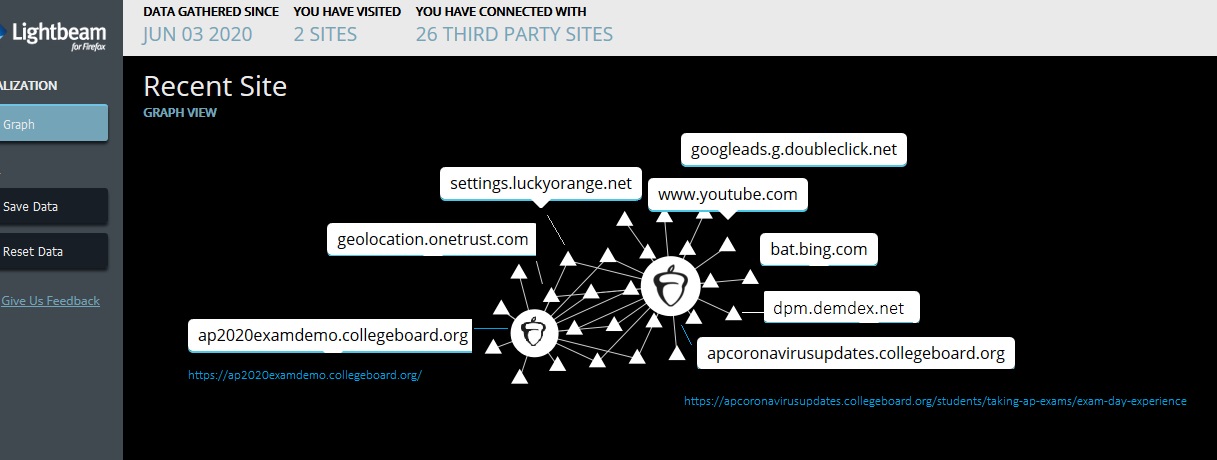

Third parties, behavioral analytics, and ad trackers on College Board websites

To see a detailed report of trackers that Lightbeam and Ghostery found on College Board websites, click here.

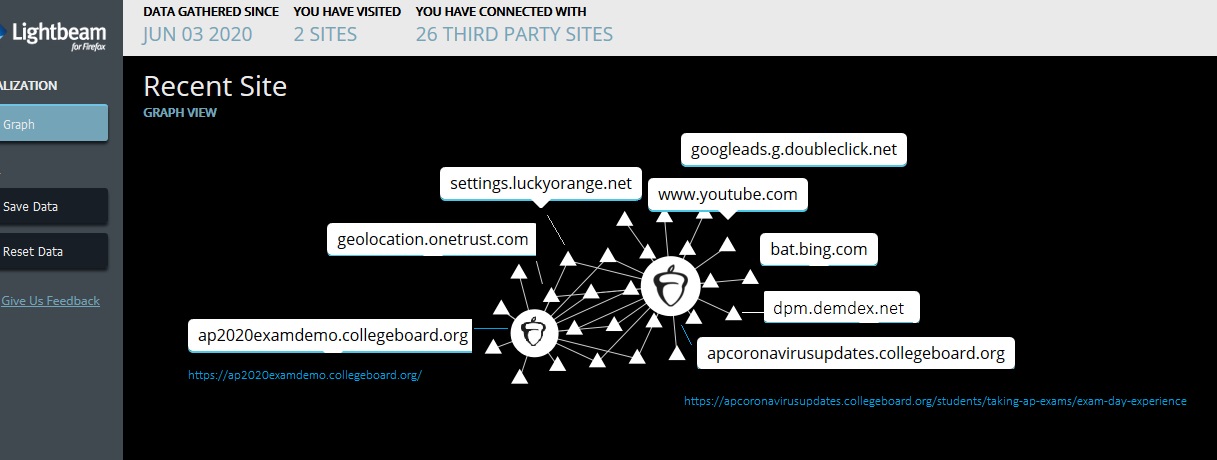

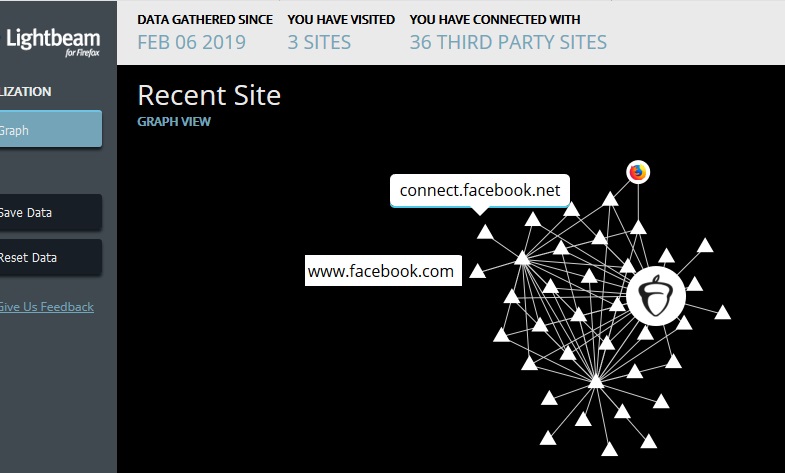

I took the practice AP Demo using the Firefox browser with the Lightbeam plug-in and Ghostery add-ons, independently; these tools are free to the public, easy to use and show third party connections and traffic between your device and the internet. I was shocked at what I saw. When I visited this College Board AP Exam Day Experience (with Coronavirus updates) webpage, I clicked on Demo which brought me to this AP2020 exam demo webpage.

I visited only these 2 College Board public facing websites, which according to Lightbeam and Ghostery, had 26 third parties including YouTube (there was a video tutorial on the AP exam day experience webpage), Google Ads (Doubleclick), Bing Ads (Microsoft), Adobe digital marketing, a Geolocation detector, 2 site analytics trackers including a first-party screen recording and analytics tool called LuckyOrange, found on the College Board’s AP Demo test page.

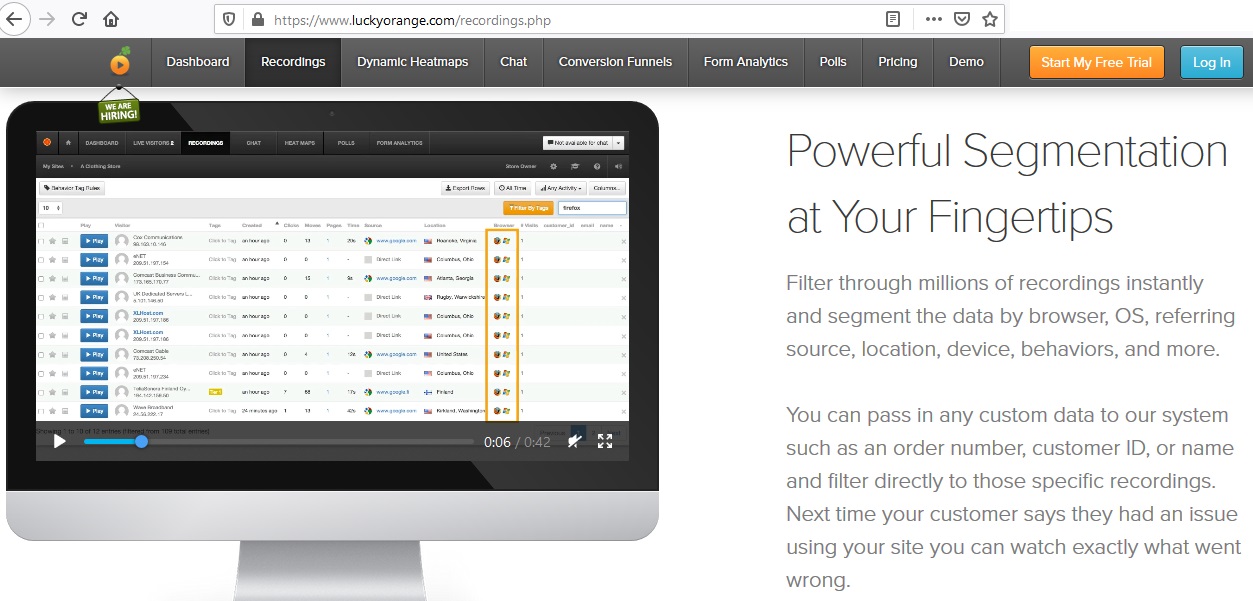

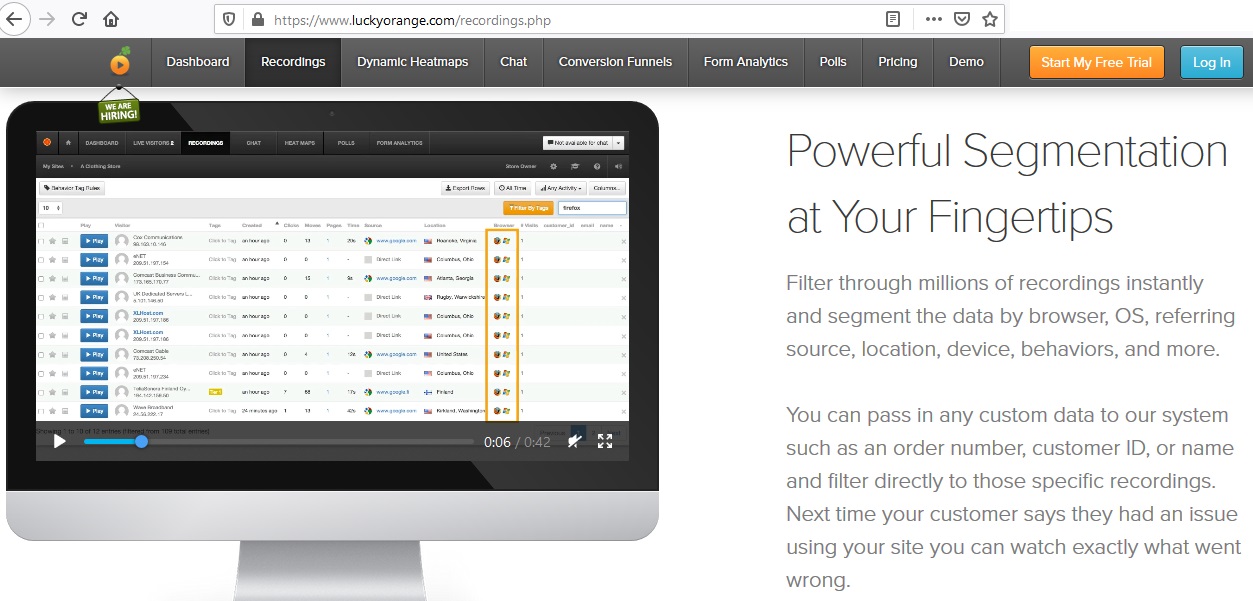

LuckyOrange: Keystroke Logger and Behavior Tags

Lucky Orange claims to let you see everything a visitor did on your webpage, offers recordings, ability to see where visitors click, how they use their mouse, and offers keystroke logging and behavior tags. The Lucky Orange website says,

“Lucky Orange will automatically create a recording of every visitor to your website. …Filter through millions of recordings instantly and segment the data by browser, OS, referring source, location, device, behaviors, and more. …Watch how customers use their mouse …Segment by location. Segment by device. …Similar to a DVR, you can play back everything a visitor did.”

Why didn’t College Board disclose their use of this invasive screen recording to users? What data did College Board enable Lucky Orange to collect, and will this data be shared or licensed? Can users ask to see their Lucky Orange data and also have it deleted?

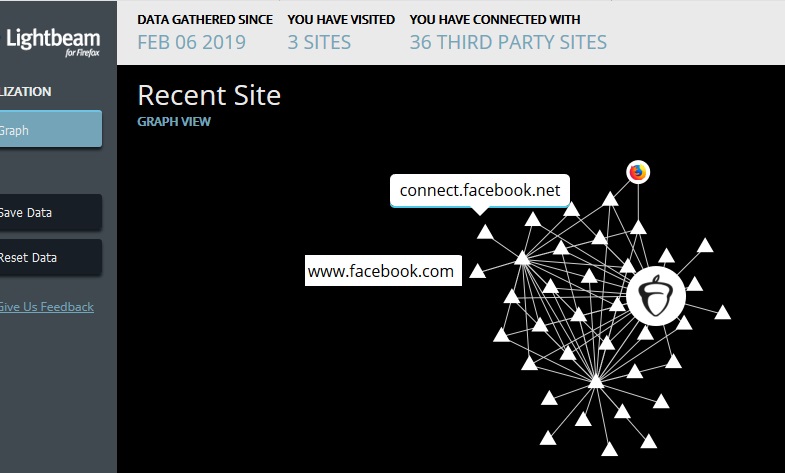

Facebook and ad trackers were also found on the SAT registration website.

We have also seen Facebook connecting to College Board websites in the past. In February 2019 while registering for the SAT via the College Board website, this student had 36 different third parties interacting, including Facebook, and Yahoo, Google, Bing, Adobe ads. Ghostery blocked 5 Advertising Trackers: Adobe Audience Manager, Adobe Test and Target, Yahoo.DOTtag, Bing Ads [Microsoft], Facebook Custom Audience and 1 Social Media Tracker: Facebook Connect and 1 Unknown Google Tracker on the College Board SAT registration website.

College Board Privacy Statement mentions sharing nonidentifiable data with Facebook & marketing companies.

When creating your account on the College Board website, clicking on Privacy Policy takes you to this College Board Privacy Center page. Further clicking on Privacy Statement brings you here with a dizzying array of options to “Learn More”. Choose Cookies and Do Not Track Signals. You will see that College Board allows third parties to collect user information; they specifically mention third parties such as Facebook.

“We do use third parties, such as Facebook, to provide information about our educational products. Only hashed, nonidentifiable information is provided to these third parties. Only individuals that have independently created an account on our site and opted in to receive marketing communications from us may receive College Board interest-based advertising on such third-party sites. No personally identifiable information is shared with those third parties.” …“The College Board participates in the Adobe Marketing Cloud Device Co-op to better understand how you use our website across various devices.” [Emphasis added]

Google/YouTube data collection are also mentioned. Why isn’t Lucky Orange mentioned? What other third parties are collecting student data from the College Board websites?

Note: Hashing is not anonymous.

It’s also important to note that according to this FTC blog, hashing data fails to provide effective anonymity. As Wolfie Christl explains in this Cracked Labs report, hashed data is not really anonymous; it’s a pseudonym that companies can use to share and match data to individual users across devices and platforms.

Did the College Board direct students to their AP website and AP Demo page, asking students to take the Demo exam, while allowing third parties to collect student information for Digital Marketing and Google ads, and also behavioral analytics, recording students’ mouse clicks and “everything they do”? What is the educational purpose in digital marketing and recording everything a user does?

I asked the College Board about AP data collection, sharing, third parties. They said that only ONE third party had access to student AP data.

In April 2020 I asked the College Board 8 questions about data collection and third party sharing associated with their new online AP tests. Here are the College Board’s April 28, 2020 answers, by way of assistance from the Colorado Board and Department of Education. See full letter and College Board’s relayed response here. One question I asked: What third parties or subcontractors will have access to student data and for what purpose? College Board’s response listed only ONE third party or subcontractor (ETS) had access to student data. (Remember, this version of My AP Terms and Conditions seemingly contradicts this College Board statement as it lists FOUR College Board AP Subcontractors: Academic Merit LLC, Alorica Inc., Educational Testing Service, Paperscorer. The College Board response doesn’t mention additional subcontractors or website third party trackers, advertisers, analytics or cloud storage companies. They declined to answer many of my questions “in order to protect the integrity of test security”. College Board’s response also said they would not require students to have their cameras turned on to take the AP exam, which contradicts the College Board President’s statement.

U.S. Senators also asked about College Board’s third parties and collection of student data.

Valerie Straus wrote about Senators’ letters sent to both databrokers and edtech companies in her August 2019 Washington Post Answer Sheet piece, Legislators ask 50-plus firms to explain how they use the ‘vast amount of data’ they collect on students. Senators received responses from many of these companies, as mentioned in this footnote comment in the Campaign for Commercial-Free Childhood and Center for Digital Democracy’s March 2020 letter which asks the FTC to conduct studies on companies collecting data from children, including ed tech companies. The CCFC letter and footnote state,

“The Senators received responses from 37 ed tech companies and 3 data brokers. …Most companies claimed they retain the information in identifiable form until the data is no longer relevant to provide the service; at that point, they anonymize the data and retain the derivative data in aggregate form. Several stated they obtained additional data from third parties like National Student Clearinghouse or social media sites, and many stated they work with third-party contractors or vendors to provide services in connection with their software or courseware (and include contracts prohibiting personal data from being used for any purpose other than providing services specific to those programs). Many companies stated that they do not disclose data collection to parents or entertain requests to delete or correct data because they understand that to be the schools’ responsibility. Finally, many companies said they store information on cloud-based servers, and only four companies said the students’ data is encrypted.”

When I reached out to the Senate for follow up, I was unable to get a copy of the College Board’s response. The Senate Aide I spoke to said they were not releasing the response letters at this time but I was able to ask questions about the responses in general. I asked if any of these companies said they do audits to ensure their third parties are using student data only as permitted by their contractual obligations. I also asked if responding companies used geolocation or collected student IP addresses, which is important with schools shifting to online learning at home with personal devices and home internet. How do these edtech companies or their third parties track and use student data from their homes?

Student data is a predictive goldmine.

When people talk about moving assessments and curriculum to online learning, I am reminded of this 2015 quote about (paper based) state tests given at the end of the year; the author said they were “Initiated in the dark ages of data poverty” but “better, faster, cheaper data is available from other sources”. What other sources? Online assessments with embedded data collecting algorithms? Online transcripts and data badges and online tools that measure and track student strengths, weaknesses, passions and emotional patterns are being promoted. Before collecting or sharing these predictive and sensitive data, parents must have equitable options, give informed consent, and the ability to refuse sharing sensitive student data with organizations and companies.

As this Parent Toolkit for Student Privacy explains,

“When students browse the internet — whether at home or school — their information is collected by online companies, bundled as consumer profiles, and then sold in the shadowy data market. Because this data has the potential to accurately predict feelings, motivations, and behaviors, it may be purchased by colleges, employers, mortgage lenders and insurance underwriters to evaluate an individual’s suitability for those services and products.”

We live in a world where schools are pushing the boundaries of surveillance technologies, with facial recognition and data collecting digital learning platforms, where machines reading our emotions is a $20 billion dollar industry. Corporations are pushing for digital identities on blockchain for everything from immunity passports to education, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is embedded in edtech tools and cloud platforms where machines can automatically make predictions about students, virtual tutors will provide “personalized” learning to students, and algorithms are keeping students out of college. We have teachers conducting brain scans in the classroom, a headband that measures student brain waves, and a scarf that will buzz if the student is distracted. Researchers now suggest using digital fingerprints and personality profiles from your social media posts to predict your future job. We have K-12 online assessments that measure students’ social emotional skills and student engagement by how fast the student answers, and infers that the “lack of test engagement is a symptom around a lot of deep-rooted problems”.

Moving testing to an online platform means increased opportunity for data collection, use of artificial intelligence and data analytics. In regards to student data and online assessments, the answer is not more data or online tests with hidden algorithms, or tests that instead measure students’ emotions, mental health, or personality. The answer is not simply a different test company. The answer is not compelling a student to agree to terms of service; privacy is not a right you can click away. College Board and other organizations, non-profit or otherwise, who are using student data must respect children’s privacy, agree to stringent data sharing contracts that require parent consent and transparency about data elements collected and shared, review algorithms for accuracy and bias before collection and processing of student data, prohibit advertising, and never sell (or license) student data. We need enforceable laws surrounding student data collection and use, with steep penalties for misuse. Privacy is a basic human right, not a luxury, and children should be protected, not profiled, stereotyped, licensed or used for profit. Organizations collecting and using student data can and should do better.