Last week, Tish James, the NY State Attorney General, won two big victories against businesses engaged in fraudulent and deceptive practices. As was widely reported, the Trump Organization was fined more than $550 M and Trump himself was barred from engaging in business in NY for the next three years. Yet the Attorney General’s victory over another huge business venture engaged in illegal practices was far less covered in the media, and in NYC, among local outlets, only the Daily News reported on it.

Last week, Tish James, the NY State Attorney General, won two big victories against businesses engaged in fraudulent and deceptive practices. As was widely reported, the Trump Organization was fined more than $550 M and Trump himself was barred from engaging in business in NY for the next three years. Yet the Attorney General’s victory over another huge business venture engaged in illegal practices was far less covered in the media, and in NYC, among local outlets, only the Daily News reported on it.

This other victory was a consent decree that the College Board signed with the AG office, in which the College Board agreed to stop the sale of personal student data of New York public school students, along with paying a fine of $750,000 – which is modest compared with the tens of millions of dollars the College Board has made from illegally selling this data over the last ten years. Here is the press release from the AG office, dated Tuesday February 13; here is an article in Reuters.

For decades, the College Board has been selling student names, addresses, test scores, and whatever other personal information that students have provided them, when they sign up for a College Board account and the Student Search program. According to the AG press release, in 2019 alone, the College Board improperly shared the information of more than 237,000 New York students. Since New York’s student privacy law, Education §2-d, calls for a fine of up to $10 per student, the penalty for selling student data during that one year alone could have equaled more than $2 million.

And yet for years, on their website and elsewhere, the College Board has also falsely claimed they weren’t selling student data. Instead they called it “licensing” data, a distinction without a difference. For years, they also claimed that they never sold student scores, though that was false as well, as they do sell student scores within a range.

The College Board urges millions of students to sign up for their Student Search program, with all sorts of unfounded and deceptive claims, including that it will help them get into better schools or receive scholarships. The reality is that their personal data is sold to over 1,000 colleges, programs and other companies – the names of which they refuse to disclose — who use it for marketing purposes and may even resell it to even less reputable businesses.

Many colleges also use the data to get more students to apply, merely to boost their selectivity rate and number of rejections, which then give them a higher ranking, a ruse reported in the Wall Street Journal and elsewhere. Though the College Board refuses to disclose how much they profit by this sale, it is likely more than $100 million a year nationally. They used to charge about 50 cents a name, but currently they charge up to a half million dollars a year or more to organizations that want access to this data.

Ever since the Education §2-d was passed in 2014, as a result of the inBloom controversy, the sale of personal student data by schools, districts, and their vendors has been absolutely banned. Since that time, New York parents along with the Parent Coalition for Student Privacy, which I co-chair, have been urging city and state officials to include an explicit prohibition against this invasive and illegal practice in their contracts with the company, and yet up to now, the city and state have refused to do so.

After the law was passed, it would be nearly five years for the New York State Education Department to draft regulations to implement it. Meanwhile, in In July 2018, an article in the NY Times revealed that an unnamed organization to which College Board had sold student data had resold it to a for-profit company that markets expensive programs to families of dubious value, and that this practice likely contributed to a thriving and largely unregulated commercial market in student data.

The article described how thousands of students attended a “Congress of Future Science and Technology Leaders” costing $985, and pointed out how much of the confidential data sold by College Board was harvested through surveys administered to students right before they take the PSATs and SATs, or when they register for the test online.

The College Board not only refused to make it clear to students that providing this personal data was voluntary, but much of the data requested was protected by a federal law called the PPRA, or the Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment, meaning that students could not be asked these questions without explicit parental consent or opt out. We had warned about this earlier in a blog post in 2017, and complained about it to the US Department of Education, which released guidance warning districts not to allow the College Board to continue this practice in May 2018.

In 2018, NYSED finally released proposed regulations for Education §2-d for public comment. The organization I co-chair, the Parent Coalition for Student Privacy, along with the statewide coalition New York State Allies for Public Education (NYSAPE), submitted recommendations on how to strengthen and clarify those regulations, as did more than 240 parents and privacy advocates.

Yet behind the scenes, the College Board was lobbying hard to persuade State Education Department officials to weaken the law with regulations that would include a special exemption to allow them to continue selling student data, with or without parental consent. Through a Freedom of Information Law request, we later received emails sent by the Board to then-Commissioner Mary Beth Elia and her successor, Beth Berlin, in 2018 and 2019, urging them create loophole for this purpose. They pointed out that 80% of students do opt into the sharing of their data, including their GPAs, ethnicity, educational interests and the like.

They claimed that asking for parent consent before they shared the data would cause 4,000 fewer New York high school graduates to attend four-year colleges every year – though they never backed up that claim. They cited an unpublished study that showed that if a student had their data shared through the Student Search process, their probability of enrolling in the college that had received that data was increased by 22 percent – without even attempting to argue that this college would be of any higher quality than any other that had not purchased their data. Moreover, when we finally got access to the study, a footnote revealed that this 22% increase only reflected an actual increase of .02 percentage points over the usual rate of .1%, since so few students actually did attend the colleges to which their data was sold.

In any case, the College Board’s lobbying efforts nearly worked, as on July 10, 2019, in the middle of summer, then- Chief Privacy Officer of State Ed Temitope Akinyemi released revised regulations for the law, without the knowledge of the state’s Data Privacy Advisory Board, on which I sit. These regulations contained a special loophole for the College Board that would allow the continuing sale of the data as long as there was parental “consent.” I, along with other parents stepped in to protest, and many parents sent in comments to the State, urging them to omit this unwarranted and damaging change in the regulations. Ad our Parent Coalition and NYSAPE wrote in a letter to NYSED after the new draft regulations were revealed,

“To create a new, huge loophole in the law that would allow the College Board, ACT or any other contractor or subcontractor to sell student data and/or use it for marketing purposes, by making the untenable claim that such sale or marketing purpose is not truly marketing if there is consent, is a drastic weakening of the law which should NOT be contemplated….

If the College Board lobbyists or its supporters would like to eliminate the prohibition of the sale or marketing of student personal data in the law, they should go to the Legislature and ask that it be amended. This should not be done through regulations or by attempting to redefine the meaning of the term “marketing.”

I then wrote an oped that was published in the Washington Post on Sept. 11, 2019, with the headline “Is New York state about to gut its student data privacy law?” In the oped, I pointed out how the data that was sold could relate to the students’ “academic and extracurricular interests, career and field of study interests, family income, and religious preferences.” A longer and more specific list of data was listed on the webpage aimed at purchasers, revealing that, depending on the test taken, the data could include student email addresses, ethnicity, GPA, sports, or “educational aspirations.” One had to dig even deeper into a SAT registration booklet, to discover that while their child’s “actual test scores” were not sold to third parties, “Colleges participating in Student Search … can ask for names of students within certain score ranges [emphasis mine].”

After the Washington Post oped was published, Betty Rosa, then the Regents Chancellor and now the Commissioner of Education, sprang into action. She called for a special meeting in Albany to take place on September 19, with top SED officials, including then-Acting Commissioner Shannon Tahoe, the Chief Privacy Officer, and representatives from the College Board, as well as Lisa Rudley of NY State Allies for Public Education and me. We were each requested to provide a one-pager beforehand, with our points about whether the regs should be altered to allow the continuation of this practice clearly laid out. (Mine is here.)

When the meeting was held, we argued these issues for about an hour, in a dark conference room in the State Education building. The representatives from the College Board maintained that they provided this data to organizations and colleges for purely charitable reasons, to help ensure that underserved students had more opportunities. Lisa and I argued among other things that the sale of this data merely contributed to an expensive marketing arms race between colleges, similar to that engaged in by drug companies, that wasted millions of dollars that could be far spent on authentic outreach to students and/or improving the quality of education they provide.

Chancellor Rosa then asked us if there were any conditions under which it would be acceptable for the College Board to continue sharing this data with third parties. I responded under three conditions: One, that the Board disclose the names of all the organizations with whom they shared the data, (which to this day they still refuse to do); two, if parents were asked and gave informed consent for this disclosure, including a clear and precise list of all the data elements the Board intended to share; and three, if the Board shared the information with these institutions for free, rather than for sale – which they should be willing to do, if their motives were as charitable as they claimed.

Chancellor Rosa then turned to the College Board, and asked them if they’d be willing to comply with those conditions, and without even a moment of pause, they said no. That was the end of the meeting. A few weeks later, SED again revised the language of the proposed regulations and took out the special loophole that had previously been inserted to allow the College Board to sell data.

And yet the illegal collection of sensitive student data and its sale by College Board continued in New York State and elsewhere. In October 2019, we wrote a blog post about this, including a fact sheet for parents, warning them to urge their kids not to answer any of the optional questions before taking these exams, and informing them that all that was required to be filled out was their name, date of birth and gender. We also warned them about the Student Search program, and advised them not to allow their children to sign up for this program, unless they wanted their names and test scores to be sold.

The College Board then sent me a letter, demanding I correct specific statements in our fact sheet, including the following. While they had asked students about their “religion activities”, a topic which is illegal without parental consent, they had recently altered this question to inquire about their “religious interests” instead. You can see their letter, my response, and their reply here.

In any case, the NYC Department of Education continued to ignore our entreaties and continued to sign larger and larger multi-million dollar contracts with the College Board every few years, for the PSAT, SAT and AP tests, without any prohibition against selling the personal student data they received as a result.

Similarly, many other districts in New York State continued to do so as well, without any apparent interest in trying to stop this illegal practice. We asked the State Education Department’s new CPO to put out guidance on the subject, and to the Attorney General office to enforce the law, even posting a petition in November 2021 asking Tish James to intervene, that received more than 700 signatures, all to no avail. Since there is no private right of action in the student privacy law, meaning parents could not sue for this ongoing violation of their children’s privacy, we were stymied.

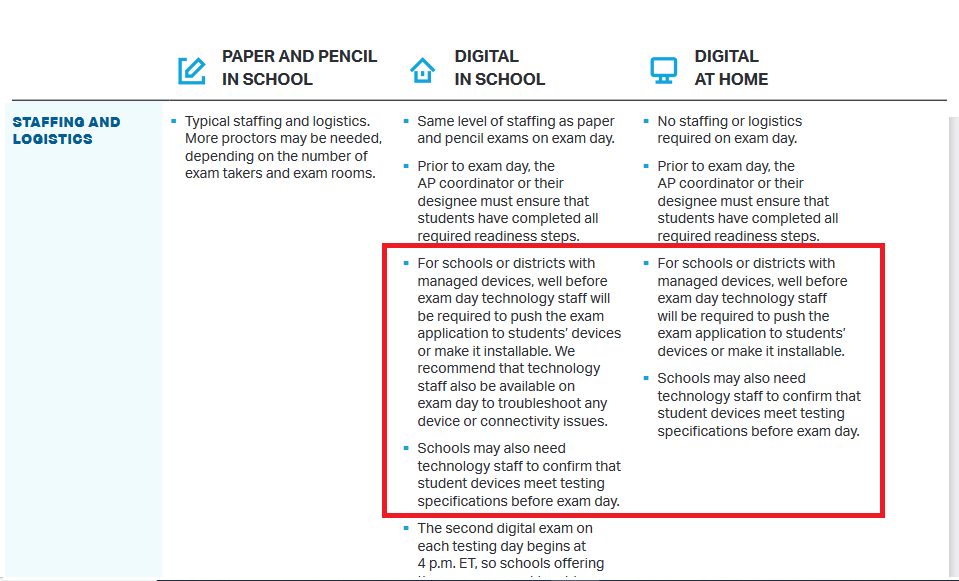

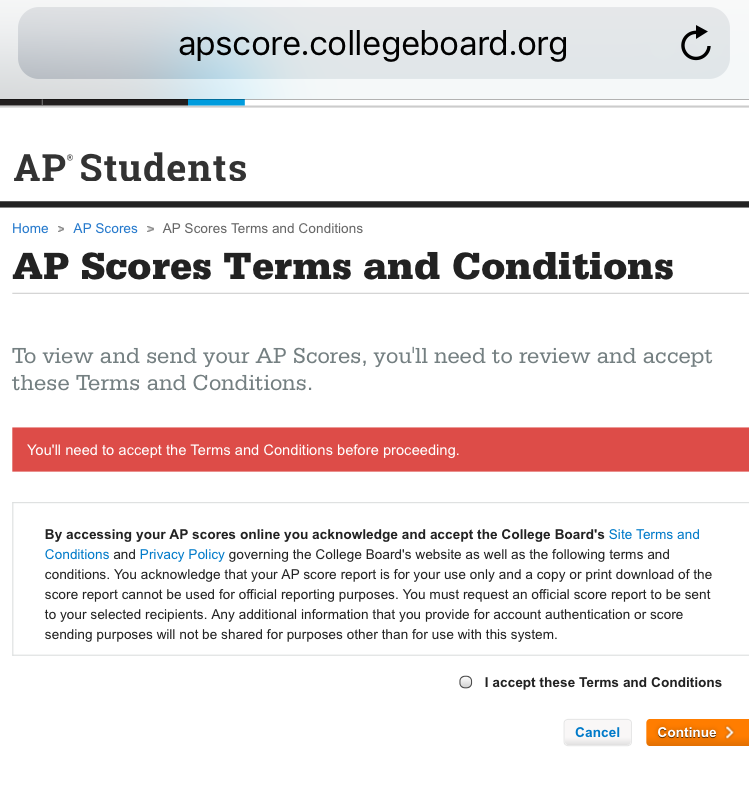

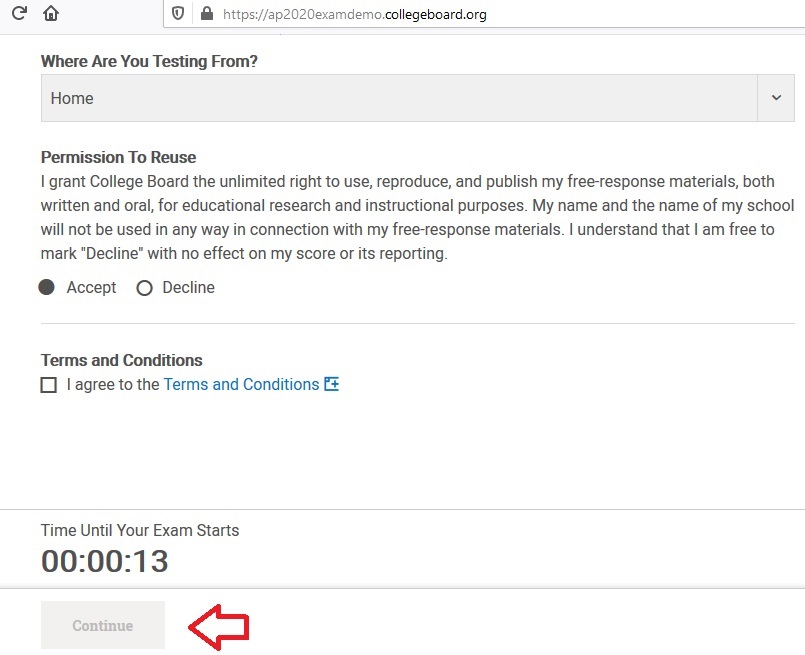

Instead, the College Board devised new evasive tricks, requiring students to sign up for their own accounts on the College Board website to take these exams and/or access their scores, even when these exams were administered by their schools with district funds. When they did sign up, students were then asked to sign a waiver, saying that they “do so in their personal capacities, not as Students of School,” apparently in order to protect the College Board from liability in having to comply with the state laws in New York and elsewhere that prohibit school vendors from selling student data.

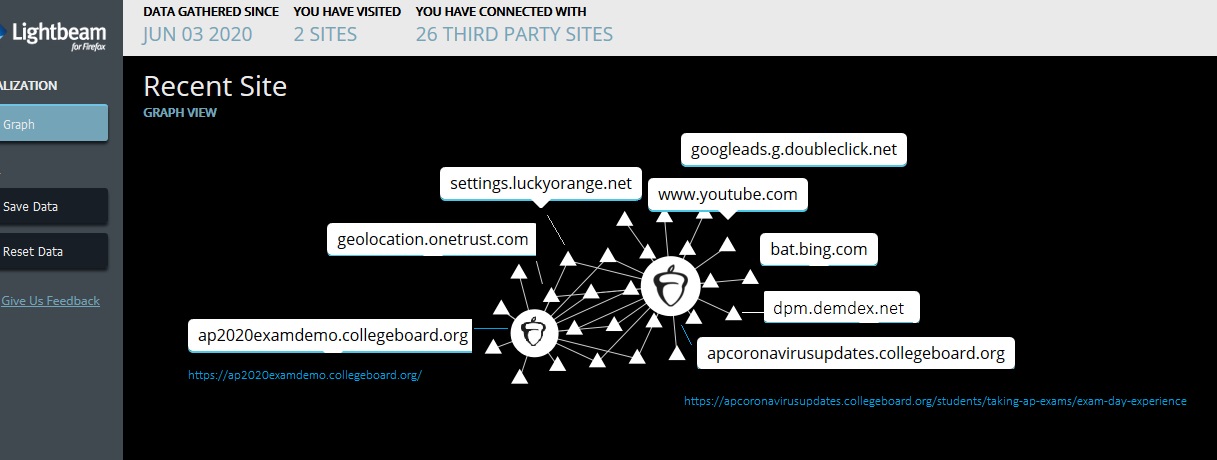

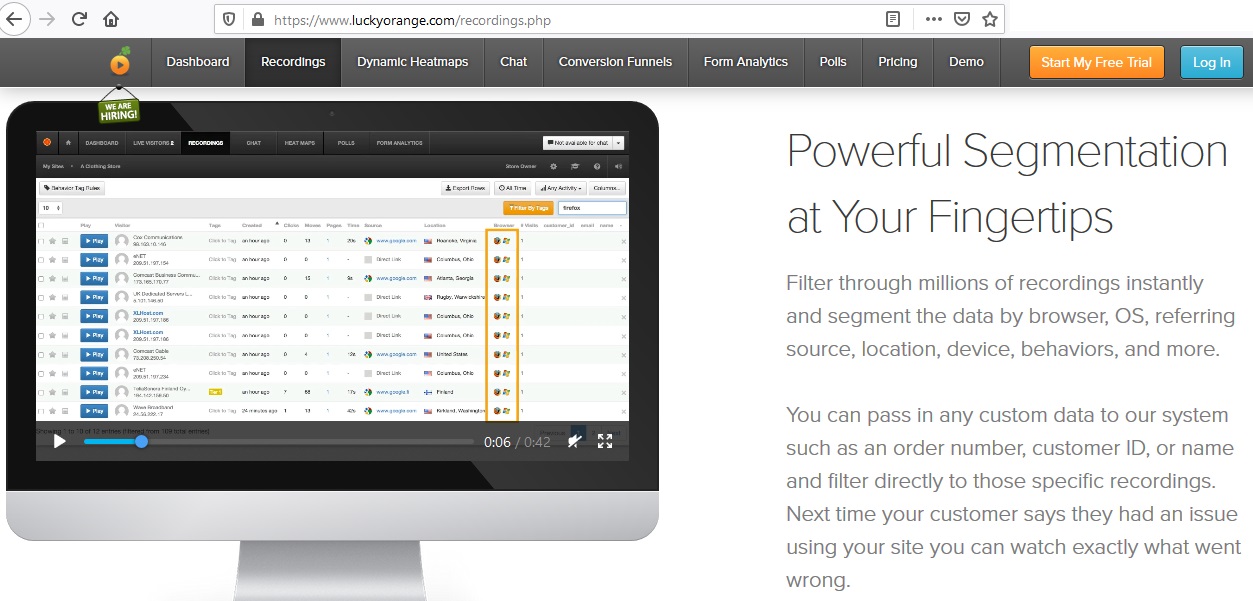

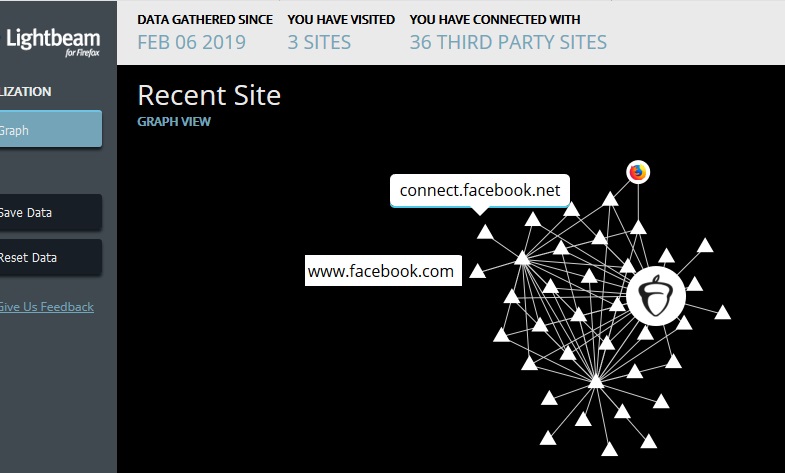

More bad publicity for College Board followed. Consumer Reports revealed how they used trackers on their website, sending information about students’ online activity to advertising platforms at companies such as Facebook and Google. We followed up with a post on our Parent Coalition for Privacy website, in which Cheri Kiesecker documented how the company utilized hidden analytics tools, recording everything a user does on its website, including keystrokes and “behavior tagging”.

She also pointed out how with their ill-gotten gains, the College Board had accumulated assets at that time of more than $1.1 billion, much of it invested in off-shore bank accounts, and paid its CEO, David Coleman, over $1.5 million per year. More recently, in 2022, according to its IRS 990, Coleman was paid more than $2.1 million per year in salary and benefits, while the Board’s President, Jeremy Singer was paid more than $1.8 million per year. The organization also provides first-class or charter travel to key employees or officers, according to Pro Publica, unusual for an education non-profit.

Then in January of 2022, we got a big break. It was announced that Tish James had asked Zephyr Teachout, a renowned anti-trust attorney, to take a leave from her faculty position at Fordham Law to work at the AG office for a year, as a “special advisor and senior counsel for economic justice.” Zephyr had run for Governor in 2014 and for Attorney General in 2018 and was highly respected for her progressive positions on a range of issues, including education and privacy.

I reached out to Zephyr with my concerns about the College Board, and starting in the summer and fall of 2022, the AG office began investigating this issue. According to last week’s press release, the College Board stopped selling the data collected in schools via PSAT and SAT exams some time in 2022 after their investigation had begun, but continued selling student data collected via AP exams through 2023.

In July of 2023, the Panel for Educational Policy approved a DOE $18 million five-year contract with the College Board for PSAT/SAT exams and other materials. In the Request for Authorization document posted on the DOE website, a section at the end entitled “Vendor Responsibility” that described just a few of the lawsuits filed against the College Board contained this statement:

In October 2022, the NYAG’s requested information from College Board to assess its compliance with Education Law section 2-D and information relating to its financial aid products. College Board advised that the matters are on-going and continues to cooperate with NYAG.

I heard nothing more about the issue for another seven months. Then last week, while lying in bed, listening to the radio in the morning on February 14 – yes Valentine’s Day – the WNYC announcer briefly reported on this consent decree.

So after ten years of advocacy, we seemed to have achieved the goal of halting this illegal practice by the College Board, at least in NY state. Yet a few questions and concerns remain, including how the Attorney General’s office intends to enforce this prohibition.

Moreover, the privacy addendum for the DOE contract with the College Board, called the “Parent Bill of Rights”[PBOR] posted on the DOE website still does not fully comply to the law. It says that the company, its subcontractors and others with whom it discloses this data will not encrypt student data “where data cannot reasonably be encrypted”, even though encryption at all times is required by Education §2-d. This is a serious violation of the law and risks damaging breaches, as have occurred too many times with DOE vendors.

Education §2-d also requires that data minimization and deletion be specified in all contracts, yet the DOE PBOR for the AP exam says the company will delete data acquired through the exam only “when all NYC DOE schools and/or offices cease using College Board’s products/services,” which could be never. The PBOR for the SAT/PSAT is even worse, as it specifies no actual date that any student data will ever be deleted. As we saw with the Illuminate breach, when nearly the data of nearly a million current and former NYC students was breached, lax data deletion contracts has allowed DOE vendors to retain the data of students far too long, even those who have long graduated from high school and left the system. It is critical that both the encryption and data deletion provisions in the College Board contracts with DOE be strengthened and enforced.

Three other points of warning to parents: There is a bill that was submitted in the State Legislature in 2021, and resubmitted this session by Senator Sanders and Assemblymember Hyndman, S4203 and A2388 that would amend the law to allow the College Board to keep selling students data. We wrote a memo in opposition to this bill in 2021. If you are a constituent of either of these legislators, please urge them to withdraw this bill.

Secondly, if your child has taken or intends to take the SAT exam outside of the school day, separate from the school context, this consent decree will not stop the sale of their data, as the state student privacy law only covers the practices of public schools, districts, and their vendors. So if you do not want your child’s personal info to be sold, including their names, scores, ethnicity, etc., to organizations and colleges, including those that may be score-optional, make sure your child does not sign up for the Student Search program.

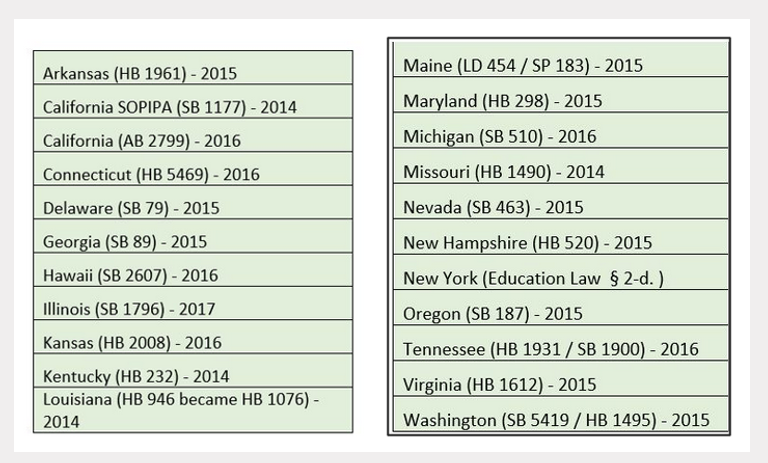

Finally, as of 2019, there were at least twenty other states which have the same prohibition against selling student data by school and district vendors, including California, Illinois, and others. Here and below is the list of such states, along with the state law that prohibited this and the year that it was passed, according to the State Student Privacy Report Card, published by the Parent Coalition and the Network for Public Education.

If you are a parent of a high school student in one of these states, please reach out to us at [email protected] with your concerns, as we plan to contact the Attorneys General of these states to urge them to act as Tish James has now done, to halt this damaging and illegal practice, and hopefully impose even bigger fines. Thanks!