A version of this report by Cheri Kiesecker, Colorado parent and member of the Parent Coalition for Student Privacy was posted this morning on the Washington Post Answer Sheet – with a response from the College Board.

PSAT/SAT day is April 5 in NYC and elsewhere when these exams are given at school to high school students. This article reveals all the very personal data the College Board collects from students without making it clear that answering most of the questions are voluntary.

Meanwhile, the CB sells a lot of this information for .42 cents per student name to colleges, for-profit organizations and even the military, for marketing and recruiting purposes – only they call it “licensing” — despite the fact that selling personal data is illegal in NY, CO and many other states.

Summary: do NOT let your children answer any questions on the PSAT or SAT other than five obligatory questions: name, grade level, sex, date of birth, and student ID number.

By Cheri Kiesecker

In schools all over the country, middle and high school students are being assigned to take PSAT and SAT assessments in a few weeks. I’m a parent and after my child’s class was asked to take the practice SAT (PSAT 8/9) this past October, I discovered that the College Board, owner of these college entrance assessments, solicits personal information from each student without parental consent.

Several weeks after the test, the College Board returned the completed PSAT answer sheets and test booklets to students once the exam had been scored and recorded. I was surprised to learn that the PSAT 8/9 answer sheet begins by asking many very personal questions of each student; though nowhere on the form or booklet does it say these questions are optional.

The PSAT 8/9 instructions printed on the answer sheet said only this:

- Use a number 2 pencil only. Print the requested information in the boxes for each item.

- Fill in the matching circle below what you write in each box. Erase errors completely.

- In very fine print, at the top of page 4 on the answer sheet, it states,

QUESTIONS TO HELP THE COLLEGE BOARD HELP YOU Your answers to the following questions will help the College Board ensure that tests and service are fair and useful to all students. Your responses may be used for research purposes and may be shared with your high school, school district and state.

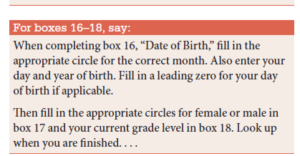

The answer sheet had spaces for the student’s name, grade level, sex, date of birth, student ID number or social security number, race/ethnic group, military relation, home address, email address, mobile phone, GPA, courses taken, and parents’ highest level of education.

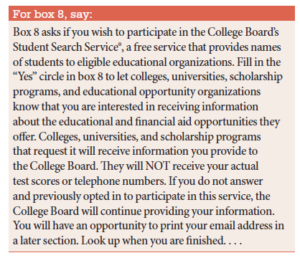

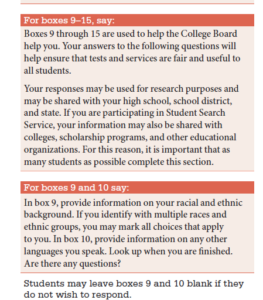

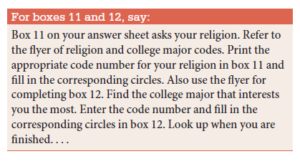

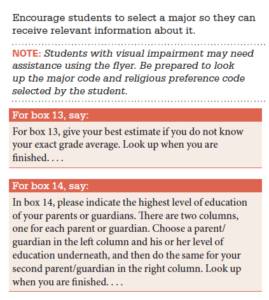

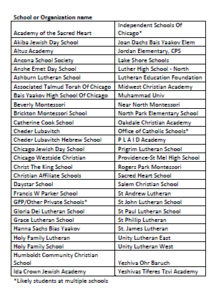

If parents or students were to take it upon themselves to peruse the College Board website, they would find a page which urges students to participate in the College Board’s Student Search Service. See the table below for a list of the data that is potentially collected and shared, depending on the specific College Board assessment, SAT, PSAT or AP. Many of these questions are also asked of students right before they take the exam, as part of the Student Data Questionnaire. (click to enlarge on the left)

As you can see, among students’ personal information collected and sold includes citizenship – a particular concern given the increased risk that undocumented students may be identified and targeted by immigration officials. In New York City, apparently because of these concerns, public schools that are administering the SAT have now been alerted not to include the Student Questionnaire as part of the test.

After searching the College Board website, I promptly contacted the College Board and asked why students are asked about their family’s race, religion or military background. What does the College Board do with this personal data? Who specifically do they share data with? You can see my questions and the confusing and evasive response from the College Board here. Oddly, it took the College Board over three months to answer. Additionally, my immediate follow up questions sent two months ago, which include asking whether they sell student data and whether it is required for students to provide their religion, are still unanswered.

In their January response, the College Board claimed that students were told which questions were optional and that students had given “express consent” to share this information. In actuality, after talking to students, parents, and administrators at the school, it was clear they were unaware that these questions were optional. Additionally, Colorado law says students must be at least 18 years old to consent to the use, sharing, or retention of their personally identifiable information.

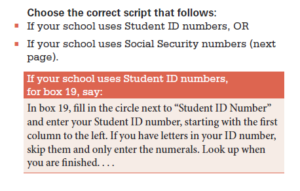

Neither the PSAT 8/9 answer sheet or test booklet informed students that most of these questions were optional, or distinguished them from the obligatory questions, demanding they fill out their name, school, etc. In fact, the “optional” questions are not identified in the PSAT 8/9 Supervisor Manual or the script which proctors are instructed to follow.

However, according to the College Board’s response to my query, only the first five questions on the answer sheet are obligatory, including student name, grade level, sex, date of birth, and student ID number. The remainder of personal questions, including race, religion, military background, GPA, home address, phone, etc. are optional.

When sitting down to take this high stakes test, how is a student able to know which questions are considered voluntary if this is not clearly marked or communicated? With the answer sheet instructions stating to fill in every box, students tend to follow suit, fearing that an incomplete answer sheet could render their scores invalid. Why does the College Board even have a space for a student’s social security number in place of student ID number, when most states forbid using social security numbers as primary identifiers? Why aren’t parents asked for consent before information about their child’s attitudes, religion and race are collected and apparently shared, accessed by outside organizations via purchased license according to the College Board website?

Under federal PPRA law, sensitive questions like religion or income, require prior informed parental consent.

Remarkably, there is no federal law prohibiting the sale of personal student data. However, there is a self-policed software industry privacy pledge in which signers promise not to sell a student’s personal information. The College Board has signed this pledge. In addition, like many other states that have recently enacted student data privacy laws, Colorado’s student data transparency and security law also prohibits vendors from selling personal student data except in the case of a merger or acquisition. Accordingly, the amended contract between the State of Colorado and the College Board for SAT and PSAT10 expressly says that the “contractor shall not knowingly….License or sell Covered Information, including PII to any third party.”

Consider the astonishing amount of data collected on students today, in particular, think of the data collected and analyzed when students take a college entrance assessment. Many states now require high school students to take the SAT in 11th grade. Some states, districts, or individual schools require students to take the practice SAT assessment in 8th, 9th or 10th, grades, in hopes of improving their scores later on the SAT. However, what many parents and schools do not know, is that their student’s personal data, including “geographic, attitudinal and behavioral information” can be profiled and accessed by organizations via a license they purchase from the College Board. Yet the College Board’s privacy policy to parents and students claims they do not sell student data. Rather, they sell a license to access a student’s personal data. What is the difference? Indeed, this distinction seems only semantics and seems deceptive.

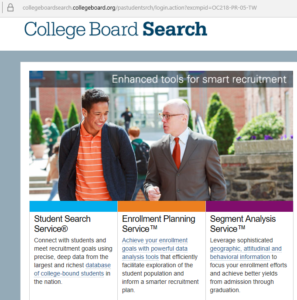

The College Board sells licenses to access the data through a tagging service called College Board Search. The Segment Analysis Service™ is one of three featured tools of the Search, along with the Enrollment Planning Service™, and the Student Search Service®. These are “enhanced tools for smart recruitment”. The College Board’s Authorized Usage Policies states, “Student Search Service in connection with a legally valid program that takes such characteristics into account in furtherance of attaining a diverse student body.”

The pricing for the College Board Search student data tagging service is $0.42 cents per student, and allows college admission professionals to identify prospective students based on factors such as zip code and race and to “Leverage profiles of College Board test-takers for all states, geomarkets, and high schools.” Segment Analysis Services is “for admission offices that need market and attitudinal information early in the recruitment process in order to better segment and target the admission pool,” and “Use Educational Neighborhood and High School Clusters as criteria when licensing names with Student Search Service, Access individual cluster factor scores. Tag an unlimited number of files…”

Which organizations buy personal student data licenses from the College Board? They are not listed anywhere on the website, but a NY Civil Liberties Union fact sheet reveals that the Department of Defense is among the institutions which buys student data for recruiting purposes.

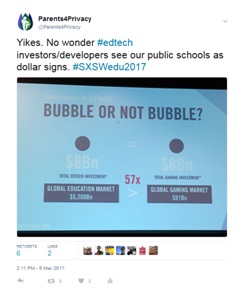

College Board, ostensibly a non-profit, had $77 million in profits and $834 million in net assets in 2015, according to Reuters. How much of that income garnered through the licensing of student data?

Please see Pricing & Payment Policies for specific information.

But why is the College Board allowed to share personal student data through the Student Search Service, in which companies are charged via a “license agreement” if this is specifically prohibited by Colorado law?

Is the College Board selling personal student data in other states, through their “license” agreements, despite having signed the student privacy pledge?

Interestingly, since I’ve started asking questions to College Board and the state, the College Board recently sent home Student Data Consent Forms for the PSAT 10 and SAT to some Colorado families the week of March 6, 2017. This is a good first step and should have been done prior to students taking the PSAT 8/9 assessment last fall. However, there is no parent signature required on these new consent forms. Why is the College Board still asking for consent from a minor student and not the parent?

Here is an excerpt of the new SAT consent form sent home to Colorado students (click to enlarge):

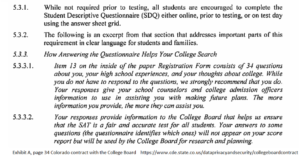

The SAT Student Data Questionnaire asks students about their personal attitudes and interests:

The SAT Student Data Questionnaire asks students about their personal attitudes and interests:

The Colorado contract with the College Board for SAT and PSAT10 states the following about this Student Descriptive Questionnaire:

Curiously, the SAT Consent Form links to instructions for the College Board’s Student Data Questionnaire which say, “The data you provide will be added to your College Board student record, even if you choose to not participate in Student Search Service.” What personal information is being “added” to a student’s record and what is the purpose? Can that information still be licensed and shared?

As reported by independent consultant Nancy Griesemer in 2015, ACT also has a lengthy pre-test survey that collects personal data from students which, combined with other data, is being used by colleges and universities to assess the student’s “Overall GPA Chances of Success” in various majors and courses, measured in terms of likely to receive “B” or “C” or in these areas. You can see what these scores look like on this updated sample ACT report. (Notice this ACT report also includes the student’s citizenship status.)

As discussed in the Washington Post last year, there’s still a lot students and parents need to know about how data is collected, shared, and accessed via licenses sold. And as Politico reported in 2014,

“Many kids also put their personal profiles on the market — whether they realize it or not — when they take college entrance exams. Students taking the SAT, ACT, Advanced Placement exams and other standardized tests are asked to check off a box if they want to receive information from colleges or scholarship organizations. Depending on the exam, at least 65 percent — and as many as 85 percent — of test takers check that box, according to the College Board and ACT. That consent allows the College Board and ACT, both nonprofits, to market students’ personal profiles…”

That struck me as almost predatory, playing on students’ hopes and fears by having them surrender their personal data. So, I wrote to the College Board and asked, what happens if students do NOT give their data to Student Search? Will this limit their ability to get into colleges? Will they still be considered for scholarships?

The answer from the College Board is important for every student, parent and school administrator to hear: “if a student does not opt in to Student Search Service it will not impact their chances at being accepted into colleges or scholarship programs in any way.” This should be printed on instructions, every test booklet, and website.

My experiences as a Colorado parent show that this frustrating lack of transparency still exists today. And it’s getting worse as increasingly, data and algorithms are being used to make decisions about students’ lives, without their even knowing. These algorithms can analyze and recombine data to make predictions about their futures. As an article in Fast Company reveals, Students’ data footprints are affecting their lives in ways they can’t even imagine:

“...Even major life decisions like college admissions and hiring are being affected. You might think that a college is considering you on your merits, and while that’s mostly true, it’s not entirely. Pressured to improve their rankings, colleges are very interested in increasing their graduation rates and the percentage of admitted students who enroll. They have now have developed statistical programs to pick students who will do well on these measures. These programs may take into account obvious factors like grades, but also surprising factors like their sex, race, and behavior on social media accounts. If your demographic factors or social media presence happen to doom you, you may find it harder to get into school—and not know why.”

Despite much opposition, a 2011 regulatory change to the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, FERPA, weakened this federal law that once protected student information from being shared without consent. FERPA needs to be fixed and parents need to be given back their rights to consent to student data sharing. State laws as well as the Student Privacy Pledge need to be scrupulously enforced so that personal student data is not sold for profit. Bottom line, parents and students after they reach 18 should own and control their own data. They should have a say as to whether and how personal information about their child is shared outside of the school walls.

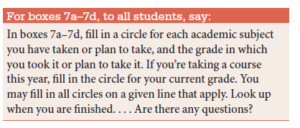

Then they ask for the student ID number or social security number, even though the latter is considered very sensitive.

Then they ask for the student ID number or social security number, even though the latter is considered very sensitive. So you can see that this script for proctors is written in the most ambiguous way possible, with voluntary questions mixed in with required ones, and no clear indication which is which or that much of this personal data will be shared with third parties for a fee.

So you can see that this script for proctors is written in the most ambiguous way possible, with voluntary questions mixed in with required ones, and no clear indication which is which or that much of this personal data will be shared with third parties for a fee.